When I started self-hosting some of my projects, I realized Git alone wasn’t enough. I needed support for large files and proper authentication, but existing solutions like GitLab or Gitea felt too heavy. They included dashboards and pull requests I didn’t need, while I wanted something modular, flexible, and under my control. That’s how GAALAFIS was born: a reference architecture that lets developers build their own tools on a solid Git + LFS foundation.

This project is as much an engineering story as a technical one. It was first an opportunity to experiment with ideas from a transversal course I took in the last year of engineering school at CentraleSupélec (2024): Complex system design. The course mainly focused on large engineering projects (planes, briges, ...) but I was trigged to see how those principles could apply to software engineering, especially as it seems so far away from the the agile principles every one seemed to have adopted.

In this course, every decision, from use cases and requirements to component choice and API design, was informed by iterative design and careful documentation. It took the form of formal documents and diagrams. It seemed heavy, but let's try.

From Use Case to Design

The initial motivation was simple: I wanted a server that could handle Git repositories, large files via LFS, and authentication for controlled access. To make the system reusable and adaptable, I needed to think about modularity, separation of concerns, and extensibility. Each requirement was iterated on, refined, and validated against the needs of hypothetical users and real workflows.

Most modern software development leans heavily on agile practices—sprints, ceremonies, minimal upfront specifications—and often avoids detailed design documents. While this works in many contexts, the GAALAFIS project became an interesting exercise in trying a different approach: defining key requirements and interfaces from the start, and iterating on them as the system evolved. Each API route, expected response, and failure scenario was derived either from real user needs or from the Git-LFS specification.

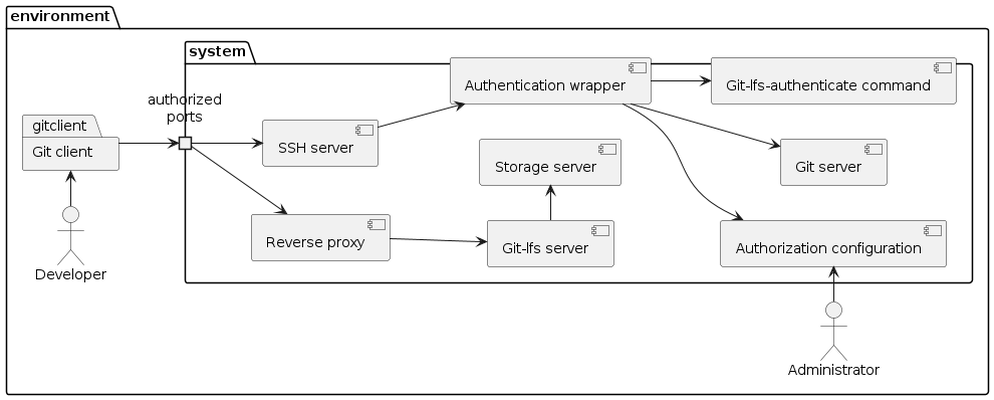

I started by exploring the context. Even if theory suggest to start only from user's perspective, we don't start from an empty worlds, and there are some industry standards and well-known usages. On the first draft, I got a few ideas formalized in a context diagram.

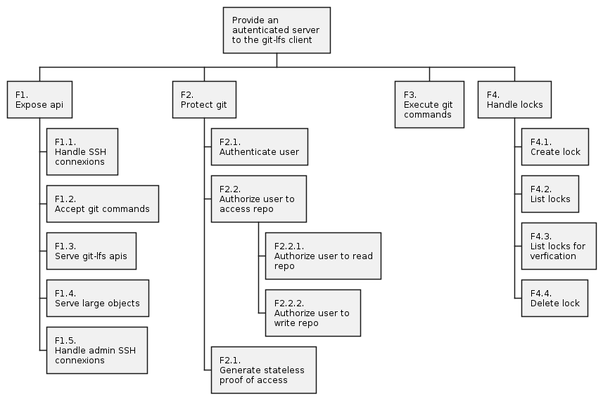

The danger with starting with this kind of draft is to take is as the final goal. And here working on user stories is the first step: validating and iterating, making as little choices as possible. I then started mapping the system from the user perspective. Developers push code, upload large files, and manage locks without any graphical interface. From these interactions, functional and non-functional requirements were derived. Every API, every expected response, and every failure scenario was traced back to either a user need or the Git-LFS specification.

This lead to various levels of functions

These functions are used to derive requirements, in various levels of details.

Architecture and Components

GAALAFIS relies on a combination of existing tools and custom components to satisfies the requirements, and now is the time to choose them. Some are just industry standards, and don't requires a lot of thinking. Other need to be carefully chosen, and some need to be crafted.

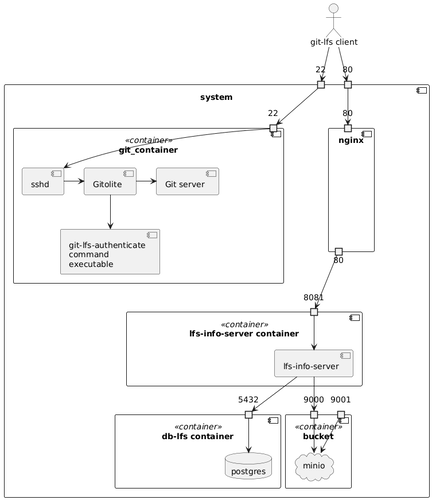

The main chosen components are:

- Gitolite, which manages repositories and SSH-based access control.

- Git-LFS server, which handles large file storage and lock management.

- Custom JWT signer, bridging Gitolite and the LFS server to authorize requests.

- PostgreSQL, storing lock metadata.

- MinIO or S3, hosting LFS objects.

- Nginx, which exposes only required endpoints and manages rate limiting.

The system is designed for modularity. The LFS server can run in a “full” mode, with batch, file, and locks APIs enabled, or a minimal mode that exposes only the required features. Each backend implements a clearly defined interface, making it possible to swap storage or change authorization strategies without altering the rest of the system.

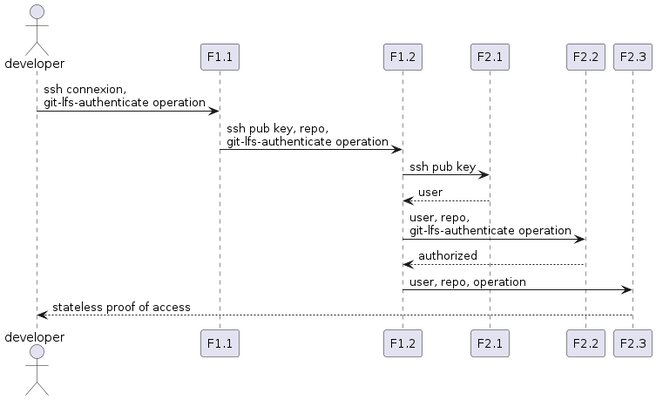

Authentication and Authorization Flow

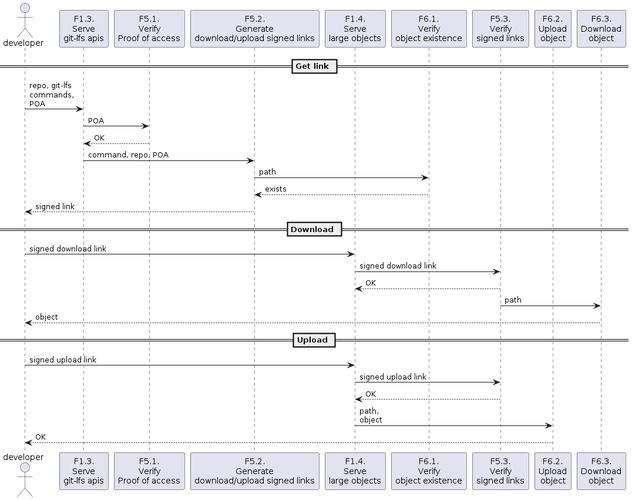

One of the most interesting challenges was combining Git and LFS authorization in a seamless way. When a user runs a Git-LFS command, the client first connects to Gitolite via SSH. Gitolite verifies the user’s key and issues a signed JWT token corresponding to the requested repository and action. The LFS server then validates this token before executing the requested operation.

This design keeps Gitolite as the single source of truth for permissions, while the LFS server focuses on storage and enforcement. It also allows for future extensions or customizations without changing the core authentication logic.

Also, the LFS server is not expected to be the same as the server the user ssh to: the authentication shall then be stateless, so the use of signed JWT.

Then the JWT can be sent to the LFS server, that will return signed links to later download or upload files

Deploying GAALAFIS

Deployment is simplified using Docker Compose. Each component runs in its own container, secrets are managed securely, and only essential endpoints are exposed externally. Gitolite handles SSH access, MinIO stores files, PostgreSQL manages locks, the LFS server proxies requests and enforces JWT validation, and Nginx routes traffic safely.

Because of its modularity, components can be swapped, updated, or scaled independently, making the architecture adaptable to different environments and future growth.

Lessons from the Design Process

Working on GAALAFIS gave me a firsthand perspective on the traditional V-process that goes beyond the textbook caricature. From an agile point of view, the V-model often seems rigid or outdated, but in practice, especially in engineering projects, it is inherently iterative. Every stage—requirements, design, implementation, and validation—forms a mini-V: you refine your ideas, test them, and adjust before moving further down.

In GAALAFIS, this approach shaped how I structured the architecture. I didn’t start with a complete Git + LFS server in mind. Instead, I began by defining the top-level use cases and core requirements, then iteratively descended into component-level designs: Gitolite for repository control, an LFS server for large files, PostgreSQL for locks, MinIO for object storage, and the JWT signer to bridge them. At each stage, I built prototypes, ran tests, and revisited earlier decisions when something didn’t fit.

This iterative descent-and-ascend process ensured that the system evolved coherently. It allowed me to catch mistakes at the right stage, refine interfaces, and experiment with modularity without losing sight of the overall purpose. In this sense, GAALAFIS became a small-scale example of how a structured V-like process, combined with iterative feedback at every step, can coexist with the exploratory mindset often associated with agile.

Ultimately, this experience showed me that the perceived conflict between rigorous design and agile iteration is largely a misconception. Even in a specification-driven process, iteration and learning remain central; the V-model just provides a framework to structure it effectively.

GAALAFIS is ready for experimentation. Developers can clone the repository, provide admin keys and secrets, and start the system with a single Docker Compose command. Git and Git-LFS operations then work as expected, allowing users to explore modular design, inspect authentication flows, and build additional tools on top. This project is not a finished product but mainly an exploration of designing and building technics, and a basis for further development.